My Anger

8/21/2025

In my own life, in my own sort of peculiar personality, I have found that repression is not available to me as an option. Least of all repression of anger. This may be surprising, because I am not, at the core, one of those constitutionally angry men who wander through the world with clenched jaws and veins popping at every imagined slight. My anger is different—it is not without reason, it is born of impotence, of indignation, of the absurd spectacle of being made helpless when every nerve in you knows you were right. It is the kind of anger that does not dissolve with time, that cannot be distracted away with travel or new projects or with the slow amnesia of days. Instead it waits, and then it comes back in tsunami waves, each larger and more destructive than the last, washing away whatever little shore of calm I had built in the interlude.

This is why I have come to learn that for me it is essential to either remove myself entirely from the source of irritation or to extirpate it at the root, to tear it out with whatever force is necessary. Because an irritant left in place festers, and festering is never just a metaphor. It is a carcinogen, and the cancer spreads in the mind first as a gnawing apprehension and then as a full-blown nightmare—an uninvited guest metastasizing into every corner of my life. The anger that might have been precise, even surgical, becomes diffused, indiscriminate, a haze that leaves me bipolar, more depressive, more unstable than even the usual contours of my manic-depressive disorder.

People sometimes speak of anger as if it is a fire, and if you just leave it alone it will burn itself out. In me it is more like radiation. It leaks invisibly, it contaminates everything around it, it builds up long after the visible flame has died, and by the time you realize the extent of the damage it has already entered your bones. And so I am left with the hard necessity of ruthlessness: either get away from the source or destroy the source, because anything less is to sentence myself to a kind of slow, psychological Chernobyl.

And yet—this anger is also the double-edged thing that keeps me alive. It is proof that I am not numb, not yet resigned to the colossal frauds and everyday betrayals that pass as normal life here. If I could not get angry, then I would simply dissolve into the background, a resigned man muttering half-truths in rooms where no one listens. My anger, for all its danger, is also the one honest thermometer of my being and the reason that you read this blog. It’s the only way I can tell the world I still exist, although I know nobody cares that I do, and those that know I’m still alive rather I die a slow, painful and agonizing death in destitution—which remarkably matches the insufferable situation I find myself in, when I am writing this.

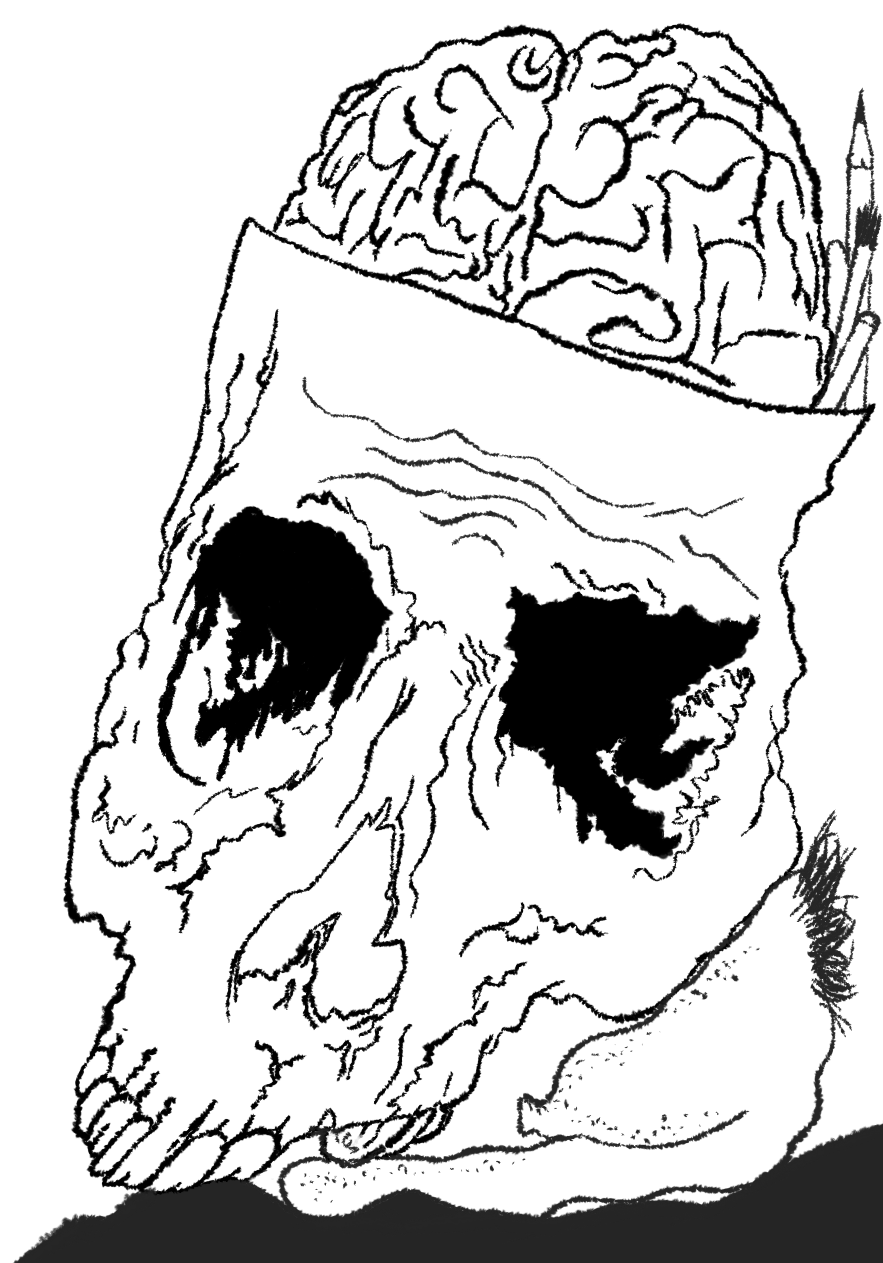

My anger is the grim graduation from one lived personal experience to another, the bitter paradox that Indians build consultancy companies, sell engineering hours, and rent out minds to fix the software and systems of corporations in developed nations, yet when you walk on the streets of India you see the same engineers stand upon crumbling sticks and patchy asphalt, a nation wobbling on rickety scaffolding of expedience instead of the dignity of structure. I have seen these projects, and I can swear they are not conceived as a labor of love or any pulse of patriotism, but as last-minute firefights cobbled together in recalcitrant haste, projects stapled with corruption, born out of necessity and panic, executed in the mood of repair rather than creation, a patchwork of shoddy half-measures dressed up as blueprint. Engineering here is not a discipline, it is a theater of damage control.

What makes it worse is not only the big structural betrayals, but the endemic personal inefficiencies in every occupation I see in India. It is incompetence at scale, incompetence with a kind of brutal banality, and it doesn’t matter what degree someone waves in your face or what prestigious office plaque they hang on their wall. The credentials, the labels, the certificates, the alphabet soup of qualifications—they obfuscate the simplest, most damning truth: these people were once students, and they never really learned. Some weren’t interested, some skipped chapters, some skipped exams, some cheated their way through, some just did enough to survive the system without ever understanding a single principle.

Open an electrical box anywhere. Look at the wiring. It is not that we lack engineering schools, or syllabi, or textbooks—those exist. It is that nobody gets what a current is, nobody knows the history of electricity, nobody cares about amperage, about metals, about standards that exist so you don’t electrocute yourself. The wiring is tangled nonsense, color coding ignored, a fire hazard waiting to happen. This rot is systemic: a mass of half-baked professionals turned loose into society with stamps of approval that mean nothing.

It was the same slop I fought when I started my IT company. Out of fifty people, only a handful knew or cared about the semantics of code. Most were louder about hours and salary than about the actual craft. They typed spaghetti into keyboards with the same blithe indifference as an electrician knotting wires like shoelaces. To me it felt like someone shitting in my mouth—because code, like electricity, is invisible until it breaks, until it burns, until the mess becomes your mess. That is when you realize the whole edifice is propped up by fakes, by the barely competent, by those who mistake credentials for comprehension.

And so the cycle continues—an India that teaches without teaching, certifies without certifying, builds without building. A country where the very idea of standards is smudged into irrelevance, leaving behind a chaos that feels less like accident and more like an inheritance, something passed down and fortified with every skipped lesson, every forged certificate, every shrug of indifference.

Which is why all the talk of India’s technological superiority strikes me as nothing but a grotesque joke, a cheap hyperbole draped over hollow bones. It’s as laughable as the patina of gentrification that now clings to our urban centers—cities literally porked up on U.S. dollar meat, fattened not by their own ingenuity but by the outsourced grunt-work of greedy Western corporations. Walk through Calcutta and you’ll see the truth plain as day: every so-called trapping of modern life is borrowed, imported, or inherited. The cup of cha from China. The rickshaw from Japan. The electric lightbulb, the railways, the telephone, the very skeleton of the city—all largesse of Europe and the United States. What we have is not an indigenous climb but a collage of foreign handouts stitched together with our own cheap thread.

We cannot even manufacture good-quality passive electronic components, let alone high-end ICs or microprocessors. We pose as a tech giant but in truth we are nothing more than a big-mouthed pimp, profiting off arbitrage, feeding on scraps, and swelling with a pride that masks only hollowness. Thankless, feckless, stupid fucks who are still clueless, who speak of the future but cannot envision one, who swagger with empty slogans while the wiring in their homes and the logic in their codes remain as sloppy as children’s Scribbles. And so the salt rubbed into my wounds is the parade of gimmick catchphrases, “Make in India” being the most nauseating of them all, a vomit-inducing banner under which we drape our failures. Each time I hear it, I feel my own desi feces crawling back up my throat, bile mixing with the rot of a slogan repeated so often it has become the official lullaby of self-deception. I grow sicker, angrier, not because I am a cynic by nature, but because this charade has no end—no iron in its bones, no blueprint beneath its skin, only a marketing agency’s wet dream for a country that cannot even wire a junction box without turning it into a fire hazard. The sickness festers because I know it is not just incompetence, it is deliberate fakery, a lie sold to the people as vision while the actual visionaries are silenced, starved, or exiled. Every syllable of “Make in India” is a fraud, a slogan that vomits me before I can vomit it.

And so, as a nation, we survive by licking China’s, Russia’s, or America’s anus, importing whatever crumbs they deign to drop, while the tiny neighborhood Asian giants—once nothing more than rice paddies and fishing villages—have leapfrogged into manufacturing excellence. If not for their hand-me-downs and our addiction to foreign crutches, we would be stranded with nothing but our proud thumbs shoved up our own brown, smelly asses—forever.

The erudition we scraped together, mostly secondhand through westernized schooling and the fossilized relics of the British baboo system, instead of being forged into a tool to carve out a prospective, prosperous nation, has been squandered on burying our young in sanctimonious rot. We have drowned generation after generation in hypocritical sermons, religious charlatanry, and a suffocating wallpaper of pseudoscience brushed on with the self-affirming varnish of cheap pride. Loud, prude, and perpetually chest-thumping, yes—but about what exactly? Peel back the garish veneer, and what remains are a handful of neglected thinkers, stray physicists, mathematicians, men and women of science left to wither in obscurity. The rest is fluff, decoy, the narcotic smoke blown from the mouths of false prophets, self-anointed gurus, and politicians whose worth is roughly equivalent to the pinworms gnawing at my asshole as I write this.

And I know people point at Indian IT engineers as if they were a slice from a different loaf. Most corporate Indians I’ve seen are little more than mustachioed bladders and belligerent udders based on their genders respectively, swollen with posturing but hollow within, experts at toggling between coy docility and counterfeit superiority depending on which mask pleases their Western overlords. They pose, they preen, they pander, all while shoving their fists elbow-deep into the rectums of their own compatriots whenever no foreign gaze is fixed upon them. The cycle repeats itself fractally, like a grotesque Russian doll—one layer of exploitation nested inside another, each uglier than the last—until you arrive at the core, where all you find is a sweatshop masquerading as a consultancy, a gulag of fluorescent lights and fake smiles. If such whorish, dick-in-dick concentration camp theaters are finally overtaken by AI, I wouldn’t call it a tragedy; I’d call it karmic symmetry, the only justice left in a system that long ago sold its soul for billing hours and PowerPoint slides.

Most people in India I have met are like harbingers of habitual hubris, smiling assassins who arrive with garlands and platitudes but carry within them the premonition of some trap, some pit they’ve already begun digging under your feet even as their palms lock warmly with yours. They are festooned fucks and celebratory cunts, draped in the costume of conviviality but lacquered with sycophancy so thick it blinds. And behind the lacquer their true artistry is at work—they are already imagining you strapped to the underside of some rancid municipal shit pipe, your mouth pried open, your dignity erased, while they squat gleefully above and drop their hot fresh turds into your defenseless throat, certain you will not spit it out but swallow, as all the generations before you have been forced to do, gagging on the national pastime of smiling betrayal. And I’m tired of being taken aback every time, whenever I even care to dig even fingernail-deep into the mascara makeup that Indians have as masks, because what’s underneath is ghoulishly unsettling and a sort of reverse cultural shock to my born-in-Calcutta-but-US-educated-and-lived-abroad brain. The layers of pretensions serve no one, are garish, and make me recoil back and never want to meet another Indian except very superficially. There’s always an ulterior motive, a knapsack of knives for backstabbing you the moment you are deficient of attention or frail, and they immediately pounce and loot at a moment’s notice all that you have, or maim you physically or mentally if they cannot finish you off. This is the nature of every kith and kin that I have endeared in my short life, and the more money you spend on them, the more benefaction, the more the treacherous scrapes that bleed you multiply in that proportion. If there’s any guarantee you are looking for, look for cruelty and wanton ungratefulness.

I had once imagined other continuities for my life, continuities overseas—corporate, academic, maybe even something quieter in retirement, or simply the open field of the unknown. But all of that has been amputated. Cut off. I am left instead with an endless continuity of something else entirely: third world structures and struggles, the permanent dysfunctions of an India that has every means to eradicate its miseries but will not, cannot, and never does. I fell through this crack, and now I suffer endlessly in the cycle of ruthless anger that no therapy, no time, no kindness can cure—only the self-flagellation of medicated numbness and polypharmacy, drugs stacked on drugs, each of them another weight pushing me closer to the ground.

I am fifty. I doubt I will last a year more. And maybe that is what gnaws at me most—that this is how it ends, not with a choice or with dignity, not with a continuation of what I once built abroad, but with the claustrophobia of being caught inside a country that manufactures cracks to swallow people like me and then congratulates itself on resilience. My anger is not some luxury of temperament; it is the only honest register of this collapse. And yet it burns me more than it burns the world around me, and soon, maybe too soon, it will finish me off entirely. Thing is, I’ve lost the will to keep myself motivated. Pills have failed, peace from interludes and wisdom from meditation and books have failed. The fabric inside is twisted beyond repair to go on, the roughened rind on the hardened fibrous core tears out of exhaustion and exasperation. People like me dying is the only right thing that would probably clear up the broth for clarity to prevail, or for the robots to take over. I am too poor, too disabled, too disenfranchised to stand up even for my own bleeding gums, let alone the fight that I had once thought I’d fight for people without transparent healthcare in India. I am outnumbered, and I am already almost dead.

I like India, I am an Indian, but these are just catch-all words, I’m not blind to the shocking reality underneath the nostalgia these words seemlessly and silently sift and snare, nostalgia built from misplaced childhood expectation or half-remembered memory from scraps of the good bits my mind has meticulously squirreled away from rare happy moments, but it’s a fiction. The real one is this: where for now eleven years after I’ve come back from the US and now half crippled I lie in Calcutta, no friend, relative or relationship has come to remember me, because they’ve known that I am a US return, an unsuitable, an unemployed, unsuccessful businessman, not worth anyone’s worth or invitation. If I die I will rot in this bed, and the people here will throw me in a dumpster if someone doesn’t pay for cremation—this is India. And here science or engineering has no place, I have no place, if I die tonight no one is going to even remember there was a romantic bengali boy who dreamed of a better India, I’ll be lost like the memory of an irritating mosquito bite, clean slate, and the new day will begin and there will be no trace of me anywhere or in anything.